3Cs 2021 Tokyo:

Asian Arts Media Round Table

This time, Asian Arts Media Roundtable will be a part of an online program of the Creators’ Cradle Circuit 2021 co-organised by Karakoa and ArtEquator with a partnership with BUoY Festival in Tokyo.

The Asian Arts Media Roundtable (AAMR), founded by ArtsEqator in 2019, is a meeting of arts editors, publishers, reviewers, arts journalists, critics, bloggers, podcasters, videocasters, academics and arts makers from Southeast Asia, East Asia and Asia-Pacific.

Panel #1:

“Critical Writing Training: Models, Methods and Pitfalls”

15th September 2021

Personal narratives on professional pathways to becoming arts writers in four Asian countries were the departure point for the rich discussion at “Critical Writing Training: Models, Methods and Pitfalls,” a panel session held on 15th September in conjunction with the “Asian Art Media Roundtable (AAMR).” This was co-organised by Karakoa and ArtsEquator as part of Creators Cradle Circuit 2021, in partnership with BUoY Festival in Tokyo. You can watch the entire panel on YouTube here.

Themes of lineage and knowledge transmission framed the presentations by Pristine de Leon (Philippines); Nabilah Said (Singapore); Hiroyuki Takahashi (Japan); and Carmen Nge (Malaysia). Guiding them was the question: how does one train to become an arts writer, and then participate in preparing others to become arts writers in their own right? At the beginning of the session, moderator Corrie Tan acknowledged its place in a world where there are concrete differentials between countries, in terms of knowledge networks and training infrastructure relevant to the panel topic.

Cultivating Arts Writing Ecosystems: Criticality and Creativity amidst Necessity By Adriana Nordin Manan

A key learning was that there is no one pathway to becoming an arts writer. The world of arts writing can absorb perspectives from a range of disciplines, and journalism was especially apparent in the presentations by Pristine and Nabilah. Their gateway to arts writing were early career positions at Hinge Inquirer Publications and The Straits Times, respectively. There, they found their way to reviewing arts events and interviewing artists, with sustained mentorship by dedicated superiors making up for any lack of formal academic training in the arts.

What stood out was the fact that Pristine and Nabilah were accorded the time to immerse themselves in their new craft. Pristine recounted extended encounters with artists at their studios or on jeepney rides. Nabilah spoke about repeated assignments to file review articles, which forced her to assume a voice of authority although it was unnerving to her as a junior writer.

Pristine de Leon shares about how interviewing artists helped her develop as a reviewer.

The shared reflections provided a more holistic perspective on journalism lineages in arts writing. Last year, cultural journalist Sharmilla Ganesan, my mentor in the Cendana-Aswara Arts Writing Mentorship programme, shared that working for a major daily newspaper taught her to write about the arts in more accessible language and economise on words at the same time. Interestingly, Nabilah shared that in her experience, the need to be economical and assume a voice of authority in media risked creating a sense of writing against a checklist or the templatisation of reviews, if you will. Supplementing this was an observation by Carmen, who teaches at the Faculty of Creative Industries, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR). She observed that if taught too prescriptively, core journalism concepts such as the 5W’s and 1H can end up producing standard, unimaginative stories. According to Carmen, this can also limit a writer’s ability to question, which she considers one of the defining strengths of the craft in today’s world, where learning systems are increasingly visually-driven.

When looked at together, the experiences of the two career academics on the panel – Hiroyuki and Carmen – offered interesting possibilities in teaching a central tenet of arts writing: critical thinking.

Nabilah Said sharing about how ArtsEquator does live events and podcasts which help demystify criticism and turn it into a conversation.

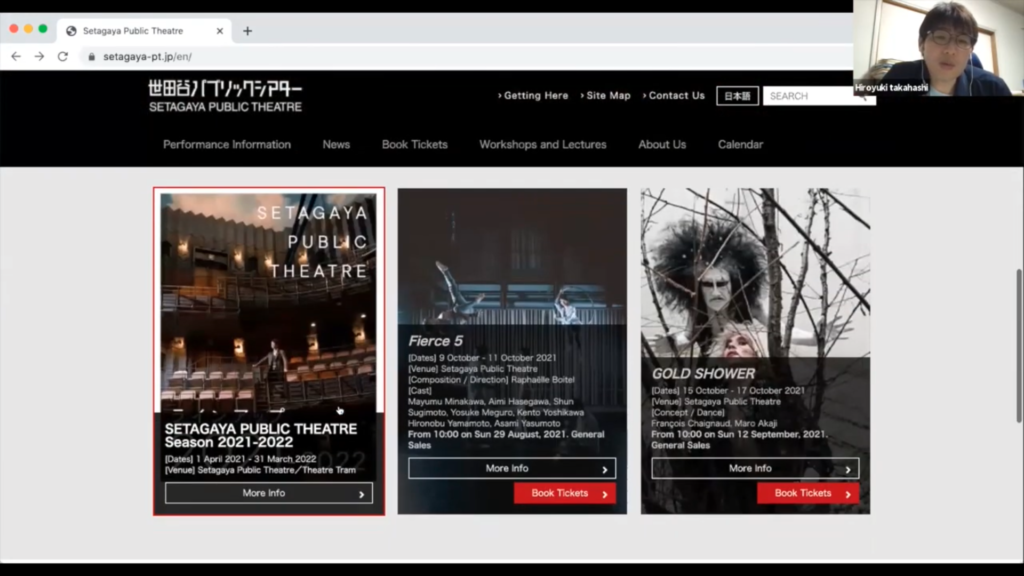

Hiroyuki’s approach can be seen as an intentional departure from the conventions of skills training. Teaching theatre criticism on a part-time basis at the Theatre Academy of Za-Koenji, Setagaya Public Theatre in Tokyo’s Setagaya City, Hiroyuki forsook the teaching of technique or skills in arts criticism or academic writing. Instead, he made it clear that his role was to provide opportunities and platforms for discussion and debate. Pleased with the programme’s ability to reach participants beyond the hallowed halls of academia, Hiroyuki shared insight on the generational divide. Among his students are young postgraduate students and senior citizens. Sometimes, Hiroyuki finds that the senior citizens write better critique essays than the students. Other times, the senior citizens struggle to understand what the students have written. One can imagine the creative tension that emerges in such an environment, and the debates it triggers in finding a common ground

Currently teaching at the Fine Arts Department of the Ateneo de Manila University, Pristine observed that her teaching style tends to chip away at presumed notions of what it means to be an arts critic. She teaches her students on the critic’s positionality, the need to question assumptions that critics must always be ‘fighting’ against artists, or that they aim for unity in perspective. Critics often disagree among themselves, she pointed out.

The challenges of teaching arts writing – an immersive craft that is best learnt by mulling – in the compressed academic calendar system were shared by Nabilah and Carmen. Apart from the insufficient time accorded, Nabilah observes a perceptible gap in academic theory too, which then impels her to design her own modules. Nabilah currently teaches a four-week arts criticism module at LASALLE College of the Arts.

Hiroyuki Takahashi sharing about his course on theatre critique at Setagaya Public Theatre.

For Carmen, the lack of time for comprehensive contextual learning is a lamentable loss. She finds that her digital native students often know, through osmosis, a lot more about the arts in bigger culturally-exporting countries compared to Malaysia. And sometimes, this knowledge is of little help in their studies of their home country’s arts and culture.

In parting, arts writing can be arrived at via different pathways, although it stands to benefit from the drive to critically engage with the culture, history and context of the works reviewed. The learning platforms do not even have to be concentrated in formal, workplace settings anymore, a pertinent point given shrinking media coverage of the arts. The doors are wide open to consider informal, smaller scale and diffuse lineages too.

The panel Critical Writing Training took place on Wednesday 15 Sep 2021, as part of Asian Arts Media Roundtable @ Creators Creators Cradle Circuit 2021 in partnership with BUoY Festival in Tokyo. It is co-organised by Karakoa and ArtsEquator. The Asian Arts Media Roundtable (AAMR), a meeting of arts writers from Southeast Asia, East Asia and Asia-Pacific, was founded by ArtsEquator in 2019.

This content is sponsored by The Japan Foundation Asia Center Grant Program for Promotion of Cultural Collaboration and Asia-Europe Foundation. The money earned from paid advertising goes towards covering ArtsEquator’s running costs and paying our writers and content creators. We have a strict policy regarding which content which can and cannot be sponsored. To read more about our editorial policy, please go here.

Adriana Nordin Manan is a writer, playwright, translator, and researcher. Born, raised, and based in Kuala Lumpur, she is fascinated by the expanse of stories as mirrors to society and monuments to the human condition. In 2019, her translation of “Pengap” by Lokman Hakim was shortlisted for The Commonwealth Short Story Prize, a first for Malay language submissions. She is currently working on her first full-length play, with themes of cultural clashes, diaspora, and family conflict. Adriana speaks Malay, English, and Spanish.

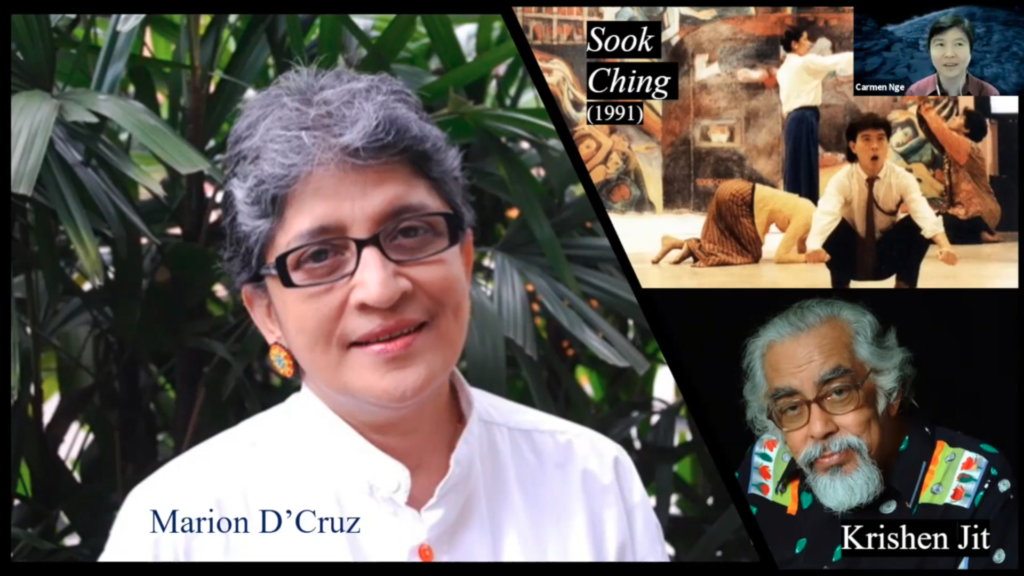

Carmen Nge speaks at length about her mentors in the Malaysian arts scene, which is how she was exposed to arts writing.

Panel #2:

“New critical vocabularies for hybrid and online performing arts, post-Covid”

22nd September 2021

If arts panel discussions are meant to reflect the times, “Critical Responses to Performance-Making in A Post-Pandemic World” positioned itself well: at this stage of the pandemic, it was less about open-ended contemplation of how the performing arts can retain vitality amidst the prohibitive circumstances, and more about sharing examples of performances that exemplify the act of moving ahead despite the barriers.

Held in conjunction with the Asian Art Media Roundtable (AAMR), co-organised by Karakoa and ArtsEquator as part of Creators Cradle Circuit 2021, the panel could be described as a whirlwind tour of pandemic-era performances, shared by panelists Uchino Tadashi and Yoshitaka Mori from Japan, Parichat Jungwiwattanaporn from Thailand and Helly Minarti from Indonesia. You can watch the entire panel on YouTube here.

Setting the stage for the discussion was moderator Carmen Nge from Malaysia (a speaker at the last panel on critical writing training), who underscored that Asian artists, having not been spared the ravages of COVID-19—though the pandemic experience differs by country—are nonetheless still persevering with their work.

Three keywords that come to my mind in reflecting on the panel are innovation, form and embeddedness. Innovation in presentation, form as a deeper reflection of the experience, and embeddedness as contextualisation of the performances within national spheres.

Prefacing his presentation, Uchino Tadashi stated something that sounded almost surreal to arts communities in other countries: the performing arts scene in Japan is now at its pre-pandemic levels, and never had to contend with strict lockdowns. As a result, Uchino commented that there is no corpus of innovations, which he described as “Zoom theatre”, to speak of from the country.

Performance Making during a Pandemic: Of Innovation, Form and Embeddedness

By Adriana Nordin Manan

(1,000 words, 3-minute read)

ビジュアル-2-1024x768.jpeg)

Nevertheless, a few examples of innovative performances were presented. In Eraser Fields written and directed by Toshiki Okada, pre-recorded performances of artists in their own living confines were presented online. The production’s website stated the guiding question as such: “Can we use theatre to present a world in which objects are equal to people rather than trapped in their usual subservient relationship?”

Currently teaching at the Fine Arts Department of the Ateneo de Manila Another example was Moshi Moshi, Not I by Kamome Machine, which was presented in person at Waseda University’s “Lost in Pandemic” exhibition. Visitors had to answer a ringing smartphone, and the person on the other line proceeded to recite lines from Samuel Beckett’s Not I, a short monologue centred on a stream of consciousness narration. Uchino noted how disoriented and lost it made him feel. Unsure whether the voice was live or pre-recorded, he did not know what was expected of him: to talk back, keep on listening or hang up? The boundaries between the performative and participatory were blurred.

If innovativeness is measured by how remote performances are able to reach across space to create a shared experience between performers and audience, then two out of the eight performances presented by Parichat in her sharing of recent notable works deserve mention.

Eraser Fields by chelfitsch & Teppei Kaneuji.

Source:

https://chelfitsch.net/en/activity/2020/05/eraser-fields.html

In Dance Offering by Kornkarn Rungsawang, a short piece presented as part of 14 in the Esplanade da:ns festival in Singapore this month, a Thai custom of making requests and presenting gifts to deities was simulated on a digital platform. A shrine dance was presented on Facebook Live, during which the audience could chat or interact with the admin. Offerings in the form of online stickers could be purchased and presented, and the dancer could be hired by individual audience members to perform additional routines.

Part of the Bangkok International Performing Arts Meeting (BIPAM) 2021, A Perfect Conversation was a joint performance by Thailand’s Sasapin Siriwanij and Eng Kai Er from Singapore. Billed a “multi-platform, online interactive experience,” it used Google Docs, video clips and the platform Pheedloop to allow the audience to interact with the performers while they viewed the pre-recorded performance together. You could call it a concurrent performance and audience talkback. (Read ArtsEquator’s review about the work here.)

In her reflections as a guest jury member for Helatari, a dance festival organised by Jakarta’s Salihara Arts Centre, Helly enjoined deeper consideration of form when adapting to the online world. Beginning her presentation with an overview of the dance film genre in Indonesia, she observed that many Indonesian dancers seemed to struggle with crafting performances which could be considered “dance films”, as opposed to Instagram Live clips, for example.

Screenshot of Dance Offering by Kornkarn Rungsawang.

(Source: Artist’s Facebook Page)

Her view on the four Helatari choreographers selected from a total of 51 proposals— Densiel Lebang (Jakarta), Eka Wahyuni (Yogyakarta), Krisna Satya (Bali) and Leu Wijee (Jakarta)—was that each demonstrated distinct experimentation vis-à-vis form and presented their own language and limitations to explore. For example, in her piece Pesona, Eka Wahyuni appeared more conscious of the role of the camera as a collaborator, or as its own entity with a gaze that needs to be negotiated with as part of the choreography.

Embeddedness refers to the notion that the arts is never far from society. The arts reflect and are constrained by society, and also amplify the latter’s fault lines in times of crisis. Speaking of global division in the form of technology divergence, Yoshitaka Mori used the example of China, where Zoom is not available. In his experience, sharing art with Chinese audiences is then obstructed.

Screenshot of Pesona by Eka Wahyuni.

(Source: https://youtu.be/Wgdt05DgzHs)

An example from Japan drove home the message of how pandemic performance-making can leave many out. For the past 30 years, on New Year’s Eve Drifting Sisters/Aquarium Theatre organises a street theatre show in Yoseba, a working class area in Tokyo. However, during the pandemic, the option of going online was unavailable as the area’s residents were mainly senior citizens who did not possess smartphones. So the 30-year run ended, and the residents did not get to enjoy the performance.

The embeddedness of the arts in politics was brought up by Parichat in her presentation. She posited that during the pandemic, there were only two types of ‘performances’ in Thailand: street protests and online performances. However, she noted that protests against the military government slowed down due to the pandemic, leading to charges that the government was abusing the restrictions for political gain. It was this backdrop of sociopolitical and economic hardship that Parichat stressed, in understanding the added challenges that Thai artists had to overcome in continuing to create.

It was a statement that resonated.

The panel Critical Responses to Performance-Making in A Post-Pandemic World took place on 22 Sep 2021, as part of Asian Arts Media Roundtable @ Creators Creators Cradle Circuit 2021 in partnership with BUoY Festival in Tokyo. It is co-organised by Karakoa and ArtsEquator. The Asian Arts Media Roundtable (AAMR), a meeting of arts writers from Southeast Asia, East Asia and Asia-Pacific, was founded by ArtsEquator in 2019.

This content is sponsored by The Japan Foundation Asia Center Grant Program for Promotion of Cultural Collaboration and Asia-Europe Foundation. The money earned from paid advertising goes towards covering ArtsEquator’s running costs and paying our writers and content creators. We have a strict policy regarding which content which can and cannot be sponsored. To read more about our editorial policy, please go here.

Adriana Nordin Manan is a writer, playwright, translator, and researcher. Born, raised, and based in Kuala Lumpur, she is fascinated by the expanse of stories as mirrors to society and monuments to the human condition. In 2019, her translation of “Pengap” by Lokman Hakim was shortlisted for The Commonwealth Short Story Prize, a first for Malay language submissions. She is currently working on her first full-length play, with themes of cultural clashes, diaspora, and family conflict. Adriana speaks Malay, English, and Spanish.

Parichat shares about how street protests were a kind of performance during the pandemic.